Robert Wayne Boyink (1938-2025)

It's been nearly 10 months, and I'm still processing the loss of my dad back in January.

Here is the obituary that ran online:

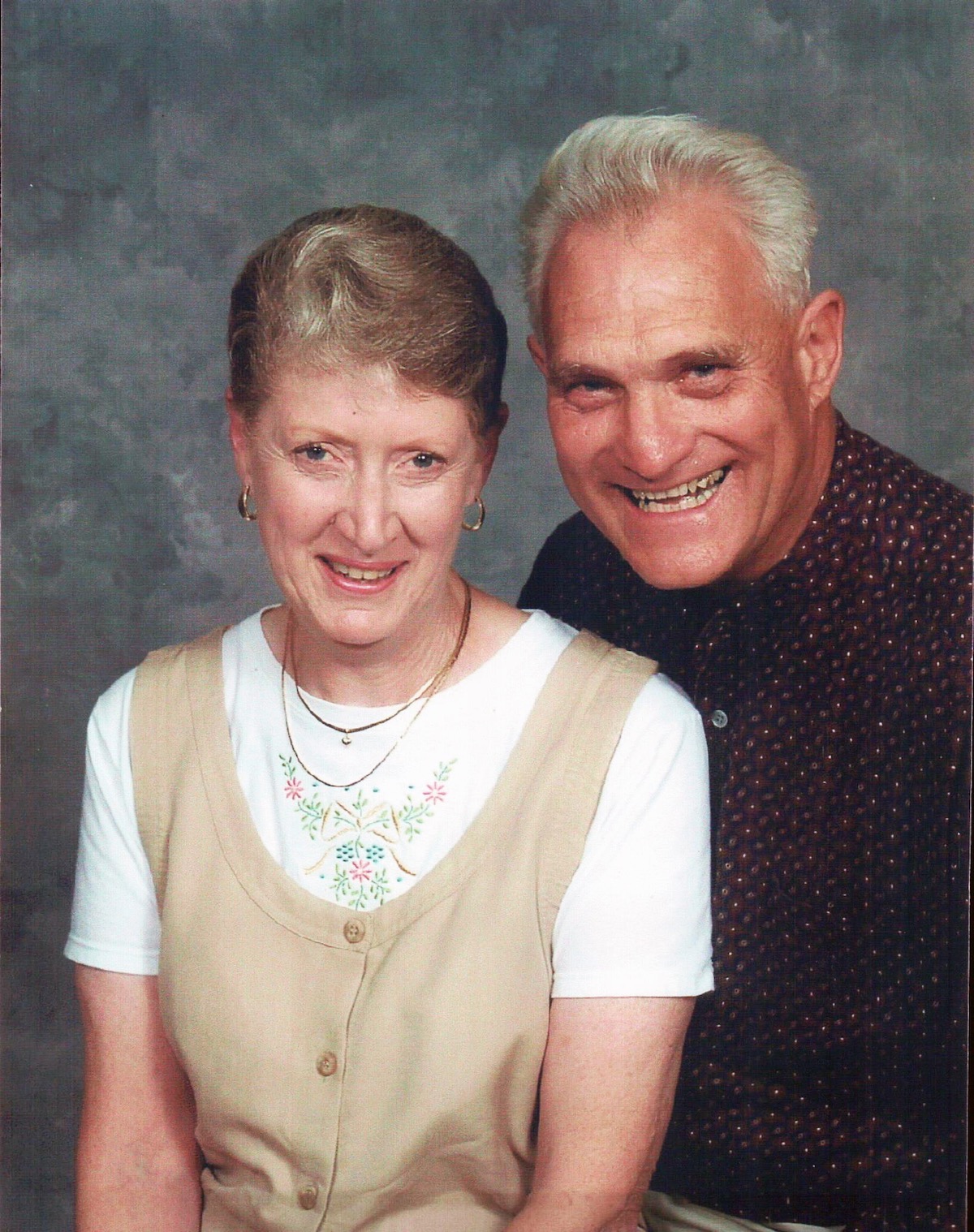

Robert Boyink, 86, passed away peacefully on Sunday, January 12, 2025, at his residence in Mission, TX. Born on May 19, 1938, in Grand Haven, Michigan, Robert led a life rich with love, adventure, and a deep devotion to family.

Robert is preceded in death by his sister Shirley Cooper. He is survived by his beloved wife of 63 years, Patricia Boyink; his sons Mike Boyink (Crissa Boyink) and Terry Boyink (Jenny Boyink) and daughter Christine VanderWall (Paul VanderWall); and numerous grandchildren who brought him great joy.

Robert is also survived by his brother, Larry Boyink (Patricia Boyink).

A dedicated waterplant operator by profession, Robert was also a gifted handyman who could fix just about anything. In his spare time, he enjoyed his hobby of ham radio, connecting with people from all over the world. A passionate traveler, Robert loved exploring new destinations with Patricia, whether they were adding unique modifications to their Jeep, camping under the stars, or square dancing together.

After retiring at 55, they split their time between the warmth of the Rio Grande Valley in the winter months and their beloved Michigan in the summer.

Robert will be remembered for his quiet strength, his warm and welcoming spirit, and the unwavering love he had for his family. He touched the lives of all who knew him and will be deeply missed.

Not Enough

I often think about memory and legacy, and while that obituary is all well and good (and with no offense to whoever wrote it) it doesn't tell the full story of a man.

That doesn't seem right for someone who has a web developer and writer for a son, and especially when that son also owns the boyink.com domain name.

So consider this page the place to capture more of the story of Robert Wayne Boyink.

But be forewarned - I don't have a formal process for writing this article. It's not going to be well-structured. I'll add/edit in a stream of consciousness fashion as memories come to me.

And I know it seems odd to mention dad in 3rd person form - but I don't like the idea of someone doing a web search for "Robert Boyink" and only getting results from corporate sites like Legacy.com (which is owned by a private equity firm - aka people only concerned with legacy as a means to profitability).

Robert Boyink's Funeral

Dad's funeral was very much like him. He was not a storyteller and there were no stories shared. He was a practical, non-sentimental man and there were no loud emotional outbursts. He was a church deacon, not an elder, a club member, not a club president, and there were no testimonies from people who "inspired by his leadership."

It was a simple affair, held in South Texas where my parents settled. My brother and sister were there with their spouses. My kids were there, my aunt and uncle (Dad's brother) were there, some neighbors, and some of dad's biking friends.

It was a Veterans funeral held at a Veterans memorial park in Mission. My mom wasn't able to attend, having had surgery for a fall less than a week before.

They read his name (slightly mispronouncing our sound-effect last name), did a 21 gun salute, presented the flag to my sister, and that was about it.

The Unknown Soldier

Dad never talked about his service much. I only recall seeing a few black and white photos of him in uniform, but I can't remember where I saw it. It wasn't ever in a frame up on the wall. I do also remember a photo of him taken in the Philippines seated on a little scooter with a spare tire mounted on the rear.

No old Navy buddies ever came to visit. His tour in the Philippines only ever came up when we kids uncovered stored-away trinkets from his tour there.

Later in life, I would always do a bit of a double-take when he'd stand to be recognized as a veteran at a public event. But he never wore a Navy hat or any other identifying clothes.

I always wanted to hear more about his military experience, but it rarely felt like the right time to ask.

We met the last survivor of the Bataan Death March during our RV travels, and when I told Dad about it he did comment about his time there, after WWII had ended. He said that the people in the Philippines were always friendly to him, thankful that the US had later liberated them.

But those kind of moments were rare. Dad usually lived in the moment, talking about the weather or something broken that he'd just fixed. He rarely waxed nostalgic about the past or expressed concern about the future.

Worried About Mom

He did once share his concern for my mom's heath. It was on a summer night, after dark, outside their cottage on Hess Lake in Grant, Michigan. My mom was in the middle of treatments for the cancer. Just for a moment, his defenses slipped, and he expressed his worry for her and not knowing what he would do if he lost her. But he didn't linger, noting the late hour and quickly getting up to make sure the boat was covered for the night.

Dad and Me Time

I am a middle child with an older brother and younger sister. Growing up in a distictly middle-class home that meant I was often the kid to save money on with hand-me-down bikes, hand-me-down clothes etc. And we usually did things as a complete family - so getting individualized attention was rare in a house where dad worked (and swing-shift at that.)

But there was one time I had a "just dad and me" camping trip. I must have been around 10-12 years old. I don't remember why my sister and brother couldn't go. But dad and I took our motorhome and dune buggy up to Silver Lake Sand Dunes in Michigan. I didn't have to try and win the "call shotgun" game in the dune buggy, got more turns steering it while dad ran the shifter and pedals, and got to make more decisions about what to eat at night.

Fond memories of that weekend helped me decide to schedule regular one on one "daddy and me dates" with my own children when they were about the same age. We just had donuts instead of dune buggies...

Helping Neighbors

He'd do anything for a neighbor and never take anything for it.

Tireless Grampa

Bob Boyink was a tireless grampa, always jumping up to give the kids rides on everything from his hand truck to the garden tractor to the SeaDoo. I don't think my kids ever heard the words "too tired."

Ice Cream

Bob Boyink loved ice cream so much he had a dedicated freezer for it in the garage.

The Scratched Jeep

Robert Boyink was fussy about his cars. He liked them clean and shiny. But money was tight and Dad was handy, so the cars were always old ones that he had restored and then kept immaculate.

One of those cars was a 1966 CJ5 Jeep. It was fire-engine red (Dad's favorite color for cars), with a black softtop and chrome-spoke wheels. Dad had bought it from a neighbor, fixed up some body rust, and repainted it in the backyard. It was his fun toy vehicle, a summer convertible that we could also take to the sand dunes.

Dad also had a number of trailers - a flatbed for hauling his garden tractor, a covered version for snowmobiles, and one made from the bed of a 50's-era Chevy truck. They all got stored behind a fence in our side yard. And of course, they all shared one license plate because Dad didn't like giving the state of Michigan any more money than he had to and he could only use one trailer at a time, right?

I was about 10 or 12, it was a fall morning, and Dad was out with his garden tractor, getting his trailers put away for the winter. But that spot behind the fence was also where the garden was during the summer and the ground was still soft.

His tractor kept getting stuck.

And Dad, as a younger man, could have a bit of a temper.

I don't remember what I was doing in the garage, but all of a sudden Dad came flying in on the tractor, screeched to a stop, shut it down, and stepped over to his Jeep.

He threw open the driver's door.

Which hit a bike that was hanging from the rafters next to the Jeep. The front wheel came off its hook. The bike swung down from its back wheel.

And put not just a scratch, but a deep gouge in fresh red paint of that Jeep.

Fueling Dad's already-hot mood.

He laid rubber reversing out of the garage.

I assume the Jeep was able to get his trailers where he wanted them.

But I didn't see it first-hand. I'd found refuge away from the storm.

He never said anything about the episode. I only noticed the touched-up paint on the Jeep.

A few years later, as a high-school senior, I borrowed the Jeep to pull our homecoming float. On the way to the game, I was showing off to a buddy, dropping the clutch and burning rubber in first gear.

I broke the driveshaft.

I called Dad, he came out with tools, pulled the broken rear driveshaft, put the Jeep in four-wheel-drive, and sent us on our way without so much as a strong word.

After graduating, I bought the Jeep from him. If you knew where to look, you could still see the scratch from that fall day in the garage.

But the damage had faded, along with Dad's temper.

The Bike Restoration Gone Wrong

When I was 16 I got interested in bicycling. Like, I wanted to be one of those serious bikers with the tight shorts and shoes that make you walk funny. My best friend had just gotten a new road bike light enough to lift with a finger, and I was envious.

I had a bike. But it wasn't the right bike. What I had was a bright yellow Schwinn that was so heavy I think the A-Team used one like it as a bad-guy battering ram in an episode.

I didn't go ask my parents to buy me a new bike. I knew what the answer would have been. We were solidly middle class, single income, and there was no budget for a new bike when I already had a perfectly good working bike.

But I had some money of my own. By age 16 I'd worked at a chicken farm, mowed lawns, picked blueberries, delivered newspapers, been a busboy and had started at McDonalds.

So I rode my Schwinn-tank down to the local bike store and traded it in on a shiny new lighter-weight Raleigh 12-speed road bike. I think I got $50 for the Schwinn and paid the difference from my savings.

And Dad wasn't happy. At all.

To him, trading things in to a dealer was a way to get ripped off. The dealer would just take your trade-in, spent 10 minutes cleaning it up, and sell it for twice the price. Better you should do the clean up, sell it yourself, and earn that extra money.

He drove off in his car.

And returned with my Schwinn.

I never heard what his conversation with the store owner was. But Dad was intent on teaching me a life lesson.

Dad brought my old bike into the garage and began working on it. But he didn't just do a 10-minute buff and polish job. He completely disassembled the bike. Every part got cleaned and restored. He sanded down the frame, repainted it in that same bright yellow, and got replacement decals from the Schwinn dealer. He retaped the handlebars with yellow tape to match the paint.

Dad's job as a swing-shift municipal water plant treatment operator meant he was often at work alone, and the nature of his job was mainly monitoring a wall of dials and gauges and logging what they indicated. It took maybe 20 minutes per hour.

In those remaining 40 minutes, he could work on personal projects in the plant's machine shop. Much of his bike restoration got done while he was at work.

After a week or so he'd finished the bike. And I'll admit, it looked brand new. Robert Boyink was certainly the "gifted handyman" that his obituary stated.

Now it was time to sell the bike.

But remember, this was before Craigslist. Or Facebook Marketplace.

Which meant he had to take out an ad in the local newspaper. He did, and few days later successfully sold his shiny restored Schwinn.

I don't remember exactly what he got for it. I want to say like $125. No matter the exact number, I had certainly learned a lesson.

But it wasn't the one Dad was trying to teach. Quite the opposite, actually.

I never saw the cost of the paint, decals, handlebar tape, or the newspaper ad. What I did see was the amount of time he spent, knowing even then that most people couldn't work on personal projects while at their main job. And while he was sweating away on that old bike, I was off enjoying my new one.

I was convinced that I'd made the better deal by trading in the bike.

I thought about this story years later, after I was married, had kids, had a house, and was running a web development business from our basement. Our hot water heater went out. I mentioned it to Dad and he said "well just go pick up another one and change it out. Shouldn't take more than a day."

I told Dad that I knew I could do what he suggested but it would probably take me the whole weekend because I'd never done one before. And I had client work stacked up. I could sit at my computer for a few hours and bill enough hours to cover the cost of a professional plumber to come replace the hot water heater. And I'd keep a client happy in the process.

He didn't argue, but I'm not sure he ever really understood. We just valued our time differently.

And maybe he had the better view. He always had time to help a neighbor or the church or any club he was part of. I don't think I ever heard the phrase "too busy" from him.

That's not a bad lesson for any of us to learn.

Broken Right Foot, Drives Across Country

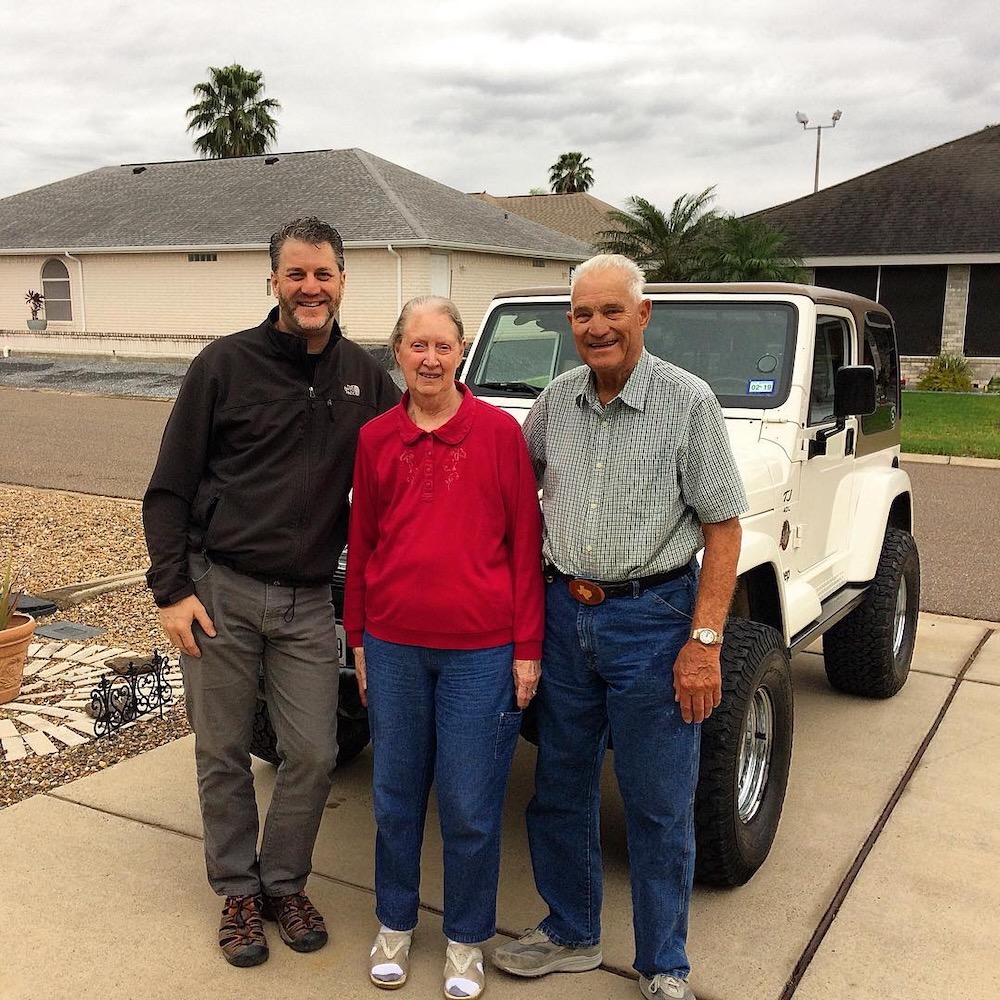

While Robert Boyink was in his 70's, he and my mom were traveling in their RV, towing their Jeep, and attending an RV/offroading rally in Colorado.

Dad loved watching TV so the RV was setup with a satellite dish. And of course, being in the mountains, he found the best reception was when the dish was up on the RV roof.

While coming back down the ladder after setting up the dish, Dad slipped off the ladder, fell, and broke his foot.

His right foot.

He got the foot attended to, but that was only half the puzzle. They were still in Colorado, and home was in Texas.

Mom wasn't comfortable driving the RV + towed Jeep.

I was self-employed at the time, and offered to fly out and drive them and the rig home. My son made the same offer. I think my older brother did as well.

But no. Dad was independent. A problem solver. He didn't want us to have to come save him.

I never heard how the satellite dish came back off the roof, but he managed to get the motorhome and Jeep all hitched up and road ready.

And drove the 1250 miles home using only his left foot.

RV Roof Surfing

I'm not sure where we were. I'd say I was 11-ish and my older brother 14. We were in the Winnebago motorhome that we did most of our family camping in.

The awning failed. It wouldn't stay rolled up while we drove down the road. Letting it hang and flap on the side would have ruined the fabric.

Dad didn't have the parts on hand to fix it.

We must have been pretty close to either our camping spot or a hardware store, because the next thing I knew my brother and I were instructed to climb up on the roof of the RV. We pulled up the awning, gathered it up as well as we could, and sat on it.

And Dad drove the RV down the road. With a concerned Mom.

It all ended without injury, of course. Dad fixed the awning and all was well. But I'll never forget the experience of parental-approved RV roof surfing.

Setting Roof Trusses with Mom

After Bob Boyink retired from the Wyoming Water Treatment Plant in Holland, MI, he bought a cottage on Hess Lake near Grant, Michigan.

As purchased, in addition to the small, two bedroom cottage, the property had space to accomodate a larger garage.

Dad set about building one large enough to store his RV, two cars, two Sea-Doos, a garden tractor, and the odd trailer. It also had shop space and a loft storage area that they jokingly called "the basement."

And when I say "set about building" it was Dad doing all of the work. He wasn't one to subcontract anything out unnecessarily. The main foundations for the garage in included more cement work was more than one person could take on, so after doing the prep work he hired a crew for that. But he had a small cement mixer and handled all of the sidewalk work outside of the garage himself.

After Dad framed in the ground-level structure, it was time to set the roof trusses in place. Dad had ordered those and they'd been delivered to the site. The trusses were wide enough to span what was basically a four-stall-wide garage.

I kept expecting a call to come help, but it never came. We happened to drive up to visit one Saturday, and as we rounded the corner by their property, this is the scene we encountered:

Dad was up on top of his framed in section.

Being a Ham radio operator, he had the experience and equipment to put up and take down radio antenna towers. One of those tools is a "gin-pole" that attaches to an installed section of tower, is long enough to accomodate the next section, and has a pulley at the top. You attach the gin pole, run a rope through the pulley, then tie the end of the rope onto your next tower section. With one person on the tower and one on the ground, the tower goes up section by section.

So Dad had his gin pole attached to his garage framing. He'd strung a rope through the gin pole pulley, and then down to the next roofing truss.

He'd attached the pulling end of the rope to the hitch on his John Deere garden tractor.

And seated on the tractor was Mom.

Dad would get things all set up, then climb up to receive the truss. He'd shout instructions to Mom over the sound of the tractor. And she'd slowly pull forward on the John Deere, lifting the truss into place.

It was hard to watch. In today's "short form video" world it looked like the setup for an epic fail.

But they made it work.

And that was classic Bob Boyink - using his knowledge and the tools on hand to get a task done without paying to hire additional help if at all possible.

Take This Job and Shove It

Bob Boyink worked at the Wyoming Water Treatment Plant in Holland, Michigan. He worked swing shift for the entire 27 years he was there. As I recall, he changed shifts in two-week rotations.

On Saturday mornings, we kids would get up, open the cupboard door over the little bill-paying desk in the dining room, and check the schedule Dad kept posted there.

Depending on the shift, he'd be home and available, home and sleeping, or gone working.

We mainly just needed to know how loud we could be. Mom and Dad's bedroom was downstairs in the basement. Our bedrooms were right over it, so if he was home and sleeping we tried to be quieter while moving around the house.

That schedule takes a toll. Later in his career he lobbied for "straight shifts" where all the employees would choose a shift and stick with it. I think he hoped the people who got the short-straw of 3rd shift ("midnights") would still be happier working one consistent shift.

I'm not sure how such a change would have been implemented and approved, but it didn't go through.

Dad stuck it out until he retired at 55 years old.

And at his retirement party, in the cafeteria area of the Water Plant, he rolled in a cart with at TV and VCR on it.

And did something I had never seen him do.

Rebelled publicly. Made a public statement about his feelings. Didn't just keep his head down.

He pushed "play."

And in front of his former boss, and his former coworkers, played this music video:

And then, not two years after he retired?

The Water Plant went to straight shifts.

Well, Bob

Be it a Sunday afternoon visit, a grandchild's birthday celebration, or stopping by because they were in town for a square dance.

After the festivities, after dessert, after the conversation had covered all of the general things it would usually cover with my parents, there always came that moment.

Mom would look at Dad and say two words.

"Well, Bob."

And that would be his cue. She was ready to get their things together and head home.

And usually, Dad would get up to start the process.

But there was a period of time, right after Mom had gone through some Chemo for breast cancer, that they would have barely arrived and settled in for the visit, when Mom would throw out a "Well, Bob."

And Dad dug his heels in.

"No. We just drove an hour to get here and I'm not ready to leave yet."

It always made me smile a little. Not that Dad was a meek pushover who let Mom rule the roost. If they were visiting it was generally because he wanted to. He packed the car. He did the driving. And he would get them home. But he usually honored Mom's way of saying "I've had enough socializing and want to go."

During Mom's chemo-years, Dad knew when to - gently - push back and get the longer visit with family that he wanted.

MsBoyink and I now work the same way. We'll be at an event, socializing with friends or family. And that moment comes when one of us looks at the clock, thinks about tomorrow's schedule, does the mental math of the time it will take to get home, get things put away, and get into bed.

And we'll say to the other.

"Well, Bob."

Grampa Chips

Bob Boyink was born into and grew up in the depression-era. His parents - my grandparents on the Boyink side - were straight working-class people who first met while slaughtering and cleaning chickens.

He and Mom brought that "thrifty Dutchmen" mentality into our lives as well. Between his skills as a DIY handyman and her sewing and crafting abilities, we lived well on his municipal salary.

But not always without a little tension.

Like with potato chips.

Woe to you if, in the Boyink house, you tried to open a fresh back of nice, whole potato chips if you hadn't first consumed the end-of-the bag chip-dust from the previous bag.

Because that was wasteful.

So, to this day, we call the last bit of potato chip pieces "Grampa Chips." And sometimes, I'll have a few in his honor. But most of the time, I'll slide those into the trash and open up the fresh bag.

Never, of course, entirely shaking off the guilt that comes with doing so.

One Termite Man and One Washer Repairman

Bob Boyink's obituary called him a "gifted handyman." That's accurate. But in this age of throw-away shrink-wrapped solutions for physical needs and apps for digital needs, I'm not sure it tells even part of the story.

Dad, along with his uncles, built the house I grew up in (here it is on Google Street View). He didn't have it built, he didn't act as general contractor and hire others to build it, he tied an apron with nail pouches around his waist, grabbed his hammer, and did the work.

He later added a barn and screened in the porch.

Motorized things were his specialty. RVs, cars, dune buggies, motorcycles and snowmobiles made up his mechanical menagerie. He did everything from rebuilding engines and transmissions to body work and paint, using an air compressor he'd made himself.

He also learned electronics. My grandma was the oldest of 13 kids, so Dad had a lot of aunts, uncles, and cousins. If anyone wanted a new television or radio, they'd buy a Heathkit version and Dad would assemble it. He was also proficient with stereos, CBs, and Ham Radios.

I can only ever remember Dad hiring two service people that came out to the house.

One was a service to spray for termites.

The other was a washing machine repairman. Our washer was acting up and for once, Dad couldn't figure out how it came apart. The repair service truck pulled in, the guy came in the house with all his tools, and quickly had the machine open and the problem exposed.

Then Dad stepped in, thanked him for his help, paid the service fee, and sent him on his way.

And completed the rest of the repair himself.

Modifying a County Fence

In my teens, one of the jobs I had was mowing the church lawn. It was a three-hour job and paid a total of $120. Dad had made a deal with us. He'd provide the equipment, we'd provide the labor, and we'd split the money. $20/hr was a pretty good gig for a teenager otherwise making $3.85/hr at McDonalds.

The mower was Dad's John Deere garden tractor, setup with a vacuum system feeding into a trailer. We also had a gas-powered string trimmer that we carried across our lap while driving the tractor to the church.

The church was in the next neighborhood over. The two subdivisions connected via a bike path which made a short drive of it on the garden tractor.

Until the county put in a staggered fence at one end of the bike path. I'm not sure if we were the cause of that, or if people were driving their cars through. Either way, we couldn't get through the new fence with the tractor.

Going around the long way would add a mile and half to the trip and that on busier roads. Too long to just drive the tractor, but too short to bother getting the flatbed trailer out to load and unload for the work.

So Dad, faced with a "forgiveness vs. permission" moment, chose the forgiveness option.

I don't remember if he did it under the cover of darkness, or was brazen enough to do it in the daylight. But he loaded up the tractor with a set of tools, drove it over to the newly installed gate, and reworked it to be large enough to get our garden tractor through.

It remained in that configuration as long as I can remember. Looking at Google Street View just now, the entire fence that Dad reworked is gone, so apparently whatever caused the county to install it in the first place is no longer an issue.

I'm guessing not enough people ride bikes through there anymore.

Almost Burning the House Down

I don't remember exactly how old I was. Old enough to be fascinated with a glow in the dark yo-yo. And have a bedspread that looked like a race car.

I don't remember how I came to be in possession of a new yo-yo.

I liked it, but I wasn't that good at yo-yo-ing. But that glow in the dark part was way cool.

I wanted to the yo-yo charged as bright as I could. I had a desk in my room (also made by Bob Boyink, as I recall) with a clip-on desk light.

I unclipped the light.

Put the yo-yo on my bed.

And put the light over it facing down.

Left the room.

And forgot about it.

I can still feel the jolt of fear that went through my body when I remembered what I had done and how long it had been since I left my room.

Running back in, my room smelled of smoke. When I pulled the upside-down desk lamp from my bed, I found a molten blob of yo-yo sitting inside a perfect 6" circle of burnt bedding. Right down to the mattress.

Dad was at work. So I brought my Mom in and showed her what happened.

She said the words that have historically stuck fear into the heart of all young boys.

"Just wait till your Dad gets home."

And I did. For several hours I sat in mental torture, imagining what my penance might be.

I remember his car turning into the driveway. The sound of the garage door going up, then going down.

The sound of the house door opening then closing. Dad entering the house. Putting away his lunchbox.

My memories blur from there. I don't recall if I had to confess. Or if Mom told him.

I don't even remember Dad's reaction, only that it wasn't nearly as bad as some of the scenes I had envisioned before he got home.

I think we were all just thankful that my bedding and yo-yo were the only casualties of my mistake.

Amen Amen Amen

Here in Tulsa, we listen to a jazz radio station. A version of the song Amen came on this morning and I immediately thought of Bob Boyink. For some reason, every once in a while, he'd start singing or whistling that song.

Not the whole song.

Just the Amen refrain.

And never any other song.

I have no idea where he learned it. We didn't sing a hymn version in church. Dad had learned to play trumpet while in high school - maybe it was one of the songs he learned on.

If we could do his whole funeral over again, a group chorus of Amen would have been a most fitting end to the service.

DIY Pet Euthanasia

Kids of Boomer Dutch parents often play a game called "how cheap were your parents?"

In love, of course.

Or at least in love once we matured past our teens and realized our parents were just doing the best they could with what they had. It also sunk in that they had often grew up in depression-era homes where money was tighter yet.

But, the game.

Basically the stereotype is (American) Dutch people like things that are cheap and shiny. So the game is trading stories about the things your parents did to save money, trying to one-up each other.

It's not uncommon to hear "we never went out to eat" or "we walked to church as much as possible" or "we rarely had straight orange juice because Mom mixed it half and half with lemonade-flavored Kool-aid to make it last longer."

And yes, all of these were true at the Boyink house.

Plus Mom made most of our school clothes, all our vehicles were second-hand, and Dad gave us TP-folding lessons to make the roll last longer.

But my last-chance, hope to win, thumb over the end of the baseball bat story was Dad euthanizing the family dog.

Sam was a Cockapoo, back when that wasn't anything other than just a small black dog. She was the dog I grew up with, and we later added her puppy Suzi to our home.

Sam had gotten old. It was that time. But Dad wasn't a "take the dog to the vet" kind of person. Like, ever. It's a good thing Sam was healthy most of her life.

Instead, Dad found a cardboard box and a tube to fit over the car exhaust pipe. We said our goodbyes, us kids went into the house, and Dad connected the tube from the car into the box. He started up the car while sitting in a garage stall. After a few minutes, he shut off the car, closed up Sam in the box, carried her to the backyard, and buried her.

For a long time I kind of felt like we had failed Sam. Like she wasn't important enough to end her life in the hands of a professional. But I came to realize she got to end her life where she spent it, and was attended to by the man whose lap she spent a lot of her life in.

And maybe in that moment, Dad was showing love in his own way.

Dad's Clothes

Robert Boyink's clothes were chosen for him by his wife. Always. I don't believe I ever saw him buy himself a shirt or pair of pants.

If he was just working around the house or hanging out he'd grab pre-approved clothes from his mom-supplied wardrobe. Mom was an excellent seamstress and would have made many of his shirts.

But if they were going out, and especially if it was out square dancing, Mom laid his clothes out for him. And he'd put them on without comment.

The reason we always heard was that Dad was colorblind, so Mom was saving him from choosing clothes that didn't go well together.

But we only ever heard that from Mom. And I never saw evidence of colorblindness in other areas of his world.

Willie B's BBQ

Bob Boyink loved his BBQ. When they were in their Mission, Texas home his BBQ of choice was Willie B's in Edinburg. He loved a side of ribs, but they would often get a loaded hot potato and split it.

We made a trip to Texas to see my parents about two months before Dad passed away. He'd had a stroke - or possibly several of them - and was mostly non-verbal and getting around in a wheelchair. We'd been told that he wasn't eating well.

They'd moved from their house into an assisted living facility, mostly eating the provided food. They also had a small fridge and microwave, so could fill in when the cafeteria food wasn't something they liked.

I knew it had been a while since he'd had his Willie B's. Getting him out to a restaurant was more of a challenge than we could take on, however, so we stopped at the restaurant, got some takeout meals, and headed to their apartment.

When we brought the food in, Dad didn't miraculously jump out of his chair and start communicating. But you could tell he knew what it was. And after getting him over to the table and setup with a fork, he went to town. Mom had to help a bit here and there but he cleaned that plate with no issues.

It was good to see him enjoy a meal. I wished we had brought more BBQ to stock their fridge with.

End of life situations are hard. I left wondering if maybe they provided more of the food he liked if he would eat more. But, it wouldn't change the fact that he'd had a stroke, was in a wheelchair, and was getting Hospice care.

We spent a couple days with them during that visit, then life called and we returned to Oklahoma.

A few weeks later we got the call that Dad had passed.

And we realized that the meal we'd brought was the last time Dad ate the food he truly enjoyed.

Unfulfilled Dream of a Campground in CO

Robert Boyink rarely talked about dreams or aspirations. But during my family's fulltime RV years he did mention wanting to do something that he never ended up doing.

We had spent some time in the Durango, CO area - camphosting for a private RV park right on the Animas River north of town.

Growing up, Dad had taken us to that area twice on extended vacations. We went in a motorhome, towing a Jeep behind and with two motorcycles on the front. He apparently loved that area of the country so much that he had thoughts of either buying or working for an RV park there.

With his limitless handyman abilities, he would have made an excellent steward of an RV park.

But he never made it. And while my parents always owned RVs, they never lived in one fulltime. Dad's parents had settled in south Texas, and as soon as Dad retired he and Mom started spending winters by them. An RV site became a park model trailer became a house in a retirement community.

By the time my grandparents had both passed away, he and Mom were too involved in square dancing, bike clubs, etc. to uproot themselves again.

Ham Radio

Robert Boyink was nothing if not a gear head. Cars. Stereos. And CBs at first. Then Ham Radio.

Dad really got into Ham Radio.

He worked up the license structure until getting his Extra. His call sign was KJ8C. He had the custom license plates. The dedicated "ham shack" in the corner of the basement. Two towers on our property - a 50 footer and an 80 footer.

To install the taller tower, Dad had to get permission from all the neighbors and a variance from the township. I think it speaks to his "do anything for anyone" outlook that not a single neighbor was against him installing that taller tower.

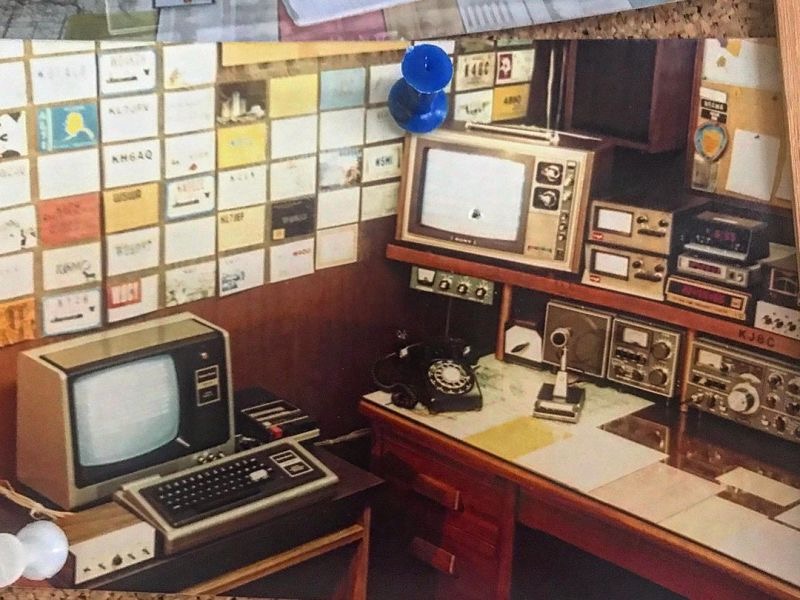

His ham shack is what people now call a "man-cave." It was maybe a 10' x 12' room. It had a desk on one side and a workbench on the other. Here's a glimpse of the desk:

Postcards from other Ham radio operators line the wall. I think they called these "wallpaper." The protocol was you'd make contact on the air, exchange mailing addresses, then send each other a card.

Lower left is our TRS-80 Model 1 computer, which Dad used for early Packet Radio (computers talking over 2-meter radio). We kids learned to program in BASIC on that machine, loading and saving programs from the cassette deck visible next to the monitor.

He had his 13" Sony TV set, and I do recall him being able to play VHS tapes on that.

He needed a telephone in there to play with "phone patches."

I don't recall specifics on the larger radios visible in the photo. The gear did continue to fill the desk and shelf to the right.

His workbench would be behind you from the perspective of the photo. It was setup with shelves and pegboards stocked with a full set of tools.

Dad was active in the local Ham radio club. We'd go on foxhunts, to hamfest swap meets, and he became active as a test administrator. The Holland-area Ham radio club always helped coordinate the Tulip Time Festival, pairing Hams up with EMTs to be there if an attendee had trouble.

I ended up getting to it as well, earning my Technicians license while I was in high school. I remember Dad had to pick me up from school to go take the test. Other students asked where I was going, and I was a bit embarrassed. Ham radio wasn't the coolest thing, but I remember them being supportive and cheering me on.

Once I had my license, I was able to show off being able to make a phone call from my car, using two-meter radio and a phone patch at the repeater. In the pre-cell-phone days that was heady stuff.

Photos of Bob Boyink

Upcoming Stories

Cars/Jeeps

RVs/Camping

Church nursery cribs

Police station overnight in RV

Tower installation/recovery

Going to work with Dad at the Water Plant

Paying for college/hot tub

2 Comments Add a Comment?

Lukas Huisman

Great story. I am a distant cousin of your mom Patricia. Although I was born with two thumbs, I can relate to the direct, stubborn and thrifty Dutchman bit!

Michael Boyink

Thanks Lukas!